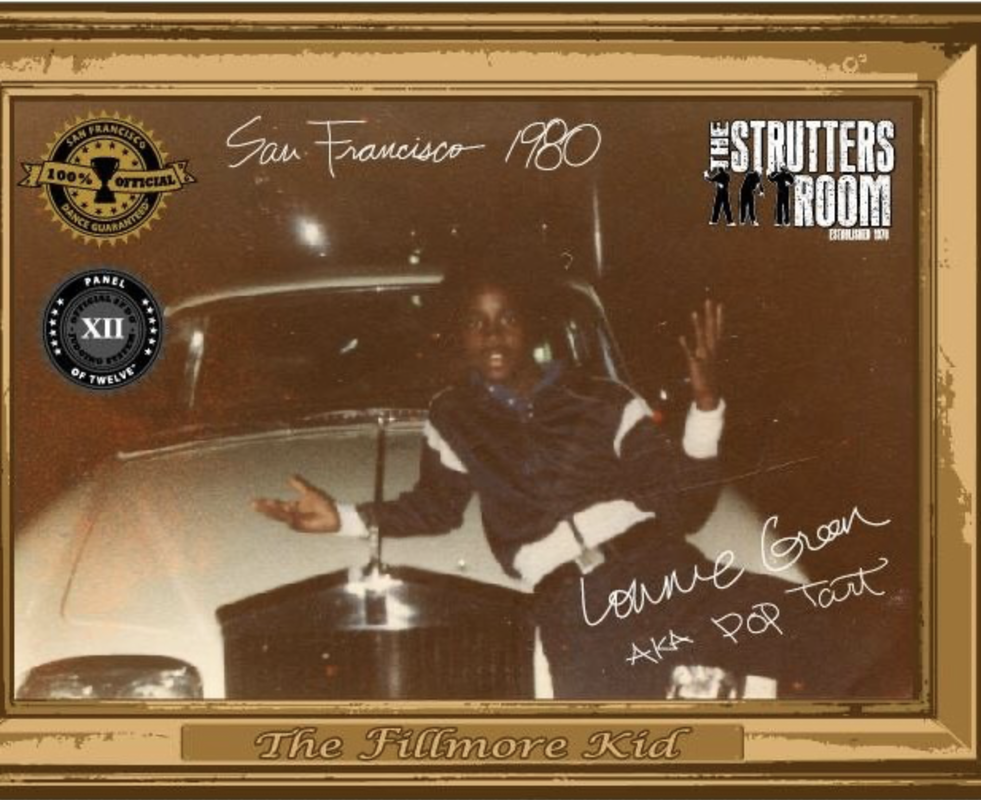

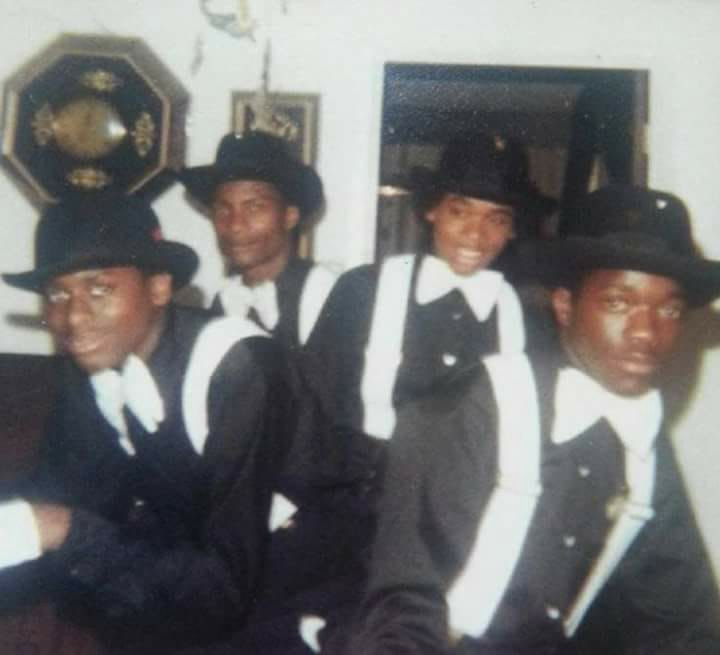

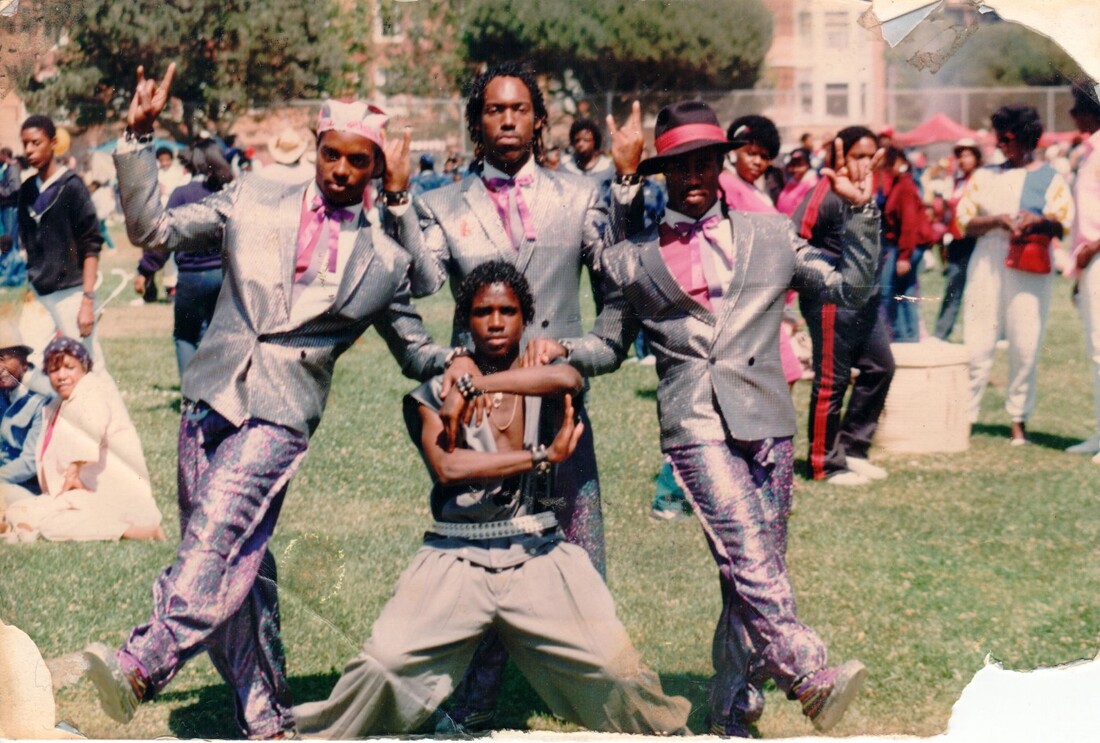

THE GIANT AWAKENING ON THE WEST COASTNow that we know why a multibillion dollar Hip Hop industry isn’t solving the problem of poverty as it grows, we can also answer why a popular California city with a $14 billion dollar budget has yet to solve its own problems by elevating the global impact of its inner-city culture…which is even bigger than Hip Hop knows. The Bay Area’s inner-city dancers of the 1960’s and ’70’s known as Boogaloos, Robotters and Strutters were an established tradition before corporate media began showcasing derivatives of their style to the mainstream public. Michael Jackson gave credit to “these beautiful children from the ghettos” for originating his moves, but TV shows like Soul Train were crediting their own featured dancers as pioneers while Hollywood ignored the street reality of their mentors who were engaged in battling police brutality and incarceration. Many dancers, like Lonnie “PopTart” Green, were so dynamic in the streets they were able to perform while incarcerated because their raw talent kept the peace better than law enforcement. This pioneering generation of competitive street dancers throughout California’s Bay Area in the 1970’s carried the spirit of revolutionary love in their bodies. They were raised by families who migrated from the South in the 1940’s to work in the shipyards, who met a different type of racism in an industrial city that was hiding the fact that it was secretly using the redlined Hunter’s Point neighborhood as a toxic waste dump site for decades. After WWII ended jobs became scarce and urban renewal projects saw Black neighborhoods like The Fillmore getting demolished to make room for new project housing. In the 1963 documentary “Take This Hammer” James Baldwin described it as “the San Francisco that America pretends does not exist.” Black San Franciscans had every ethical reason to find their own ways of resisting this new type of economic racism that Maya Angelou wrote about in her 1969 autobiography “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings”. The spirit of resistance was strong enough for California Governor to call the national guard during the uprising that occurred after a white police officer shot and killed Matthew Johnson, an unarmed black teenager in 1966. The citywide rebellion caused The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense to announce its formation just weeks later in Oakland. That revolutionary energy was naturally channeled into the competitive dance movements of kids who were literally fed by the Free Breakfast for Children program. Throughout the 1970’s, these BRS styles spread throughout Northern & Southern California through family gatherings, talent shows, intramural school events, and the state penitentiary system, eventually reaching inner-city movers in Los Angeles who blended it with their style of Locking that later became known as “Poppin” or “Poplockin”. Oakland Boogaloo even spread beyond California through the military service of dancers like Jerry Rentie, who brought the Boogaloo style to the East Coast, inspiring a young dancer named Lockatron John, who would later introduce the style at the high school of two teenagers who would become some of New York’s most respected Hip Hop dancers, Mr. Wiggles and Popmaster Fabel. By the time national television caught on to the inner-city movement and announced the emergence of New York’s own brand of project culture with its message of “Peace, Love, Unity and Having Fun”, the media adopted the term “Hip Hop” as the template for all street expression, using the South Bronx’s Universal Zulu Nation elements of “DJing”, “MCing”, “Breaking” and “Graffiti”. Hip Hop music videos like “The Message” showed an East Coast style of expression and the parallels with California were uncanny, yet distinct. It may not have been understood then, but the Fillmore District in San Francisco — known as “The Harlem of the West” in the 1940’s and 50’s — was producing the most competitive dance groups on the West Coast and could have just as easily been dubbed “The South Bronx of the West” in the 1970’s. Tragically, the Bay Area’s origin story was erased from the West Coast’s historical narrative with Hip Hop movies like Breakin 2: Electric Boogaloo, whose casting process intentionally avoided and even stole from street dancers who were too street. Instead, Hollywood producers elevated a particular network of Southern California dancers — even ignoring the stories of their own inner-city mentors like Diane Williams, aka Queen Boogaloo, and countless others — so much so that Hip Hop transplants from New York thought Los Angeles represented the entirety of California. The street dance industry was and still is an appropriative force established on 2nd & 3rd generation information intentionally disconnected from its inner-city roots on the West Coast. Hollywood shut the majority of the streets out of the Hip Hop industry from jump. As the creativity of the ghetto was being put into the public spotlight in the 1980’s, Hip Hop entertainment had children all over the world saying “I want to do that too”. Unfortunately, the solidarity of a new generation of “Hip Hop dancers” was already lost through the industry’s merging of aesthetic appeal and the corporate erasure of its inner-city Black sociopolitical origins. For example, talent pipelines like The Gong Show were forcing pioneering Boogaloo groups like “The Black Messengers” to change their name so as not to offend a larger, whiter audience, while Strutting groups like “Granny & Robotroid Inc.” were asked to change their choreographed routines for TV cameras, further removing the genre’s creators from authentically representing themselves. The erasure of cultural contribution within mainstream American consciousness is once again the product of corporate-controlled interests attempting to manufacture inner-city resilience for mass consumption. The revolutionary consciousness it keeps out of the spotlight allows subsequent generations to pursue individual success over the prioritization of communal solidarity, which prevents inner-city culture from achieving its ultimate organizational potential. That potential is untapped to this day because our “educated perspective” of the historical narrative is incomplete. California cannot be defined by East Coast standards, just like the Bay Area cannot be defined by Los Angeles, San Francisco by Oakland, nor Fillmore by Hunter’s Point. Pretending otherwise fails to capture the depth of the Black experience in America. The inner-city response across the country to the 1950's and ‘60’s failed federal urban renewal policies connects all inner-cities politically, but without the context of the West Coast’s unique response to the nationwide socio-economic injustice, Hip Hop’s unifying potential is critically limited. This is why in 2019, a network of artists, organizers, educators and activists in California launched the first statewide Hip Hop education initiative in the country called H2E2, the Hip Hop Education & Equity Initiative, to help youth in public schools not only find their voice but reconnect to their local history and learn how inner-city cultures developed after the 1960’s. Hip Hop education is an emerging professional field and it is important that its resources cover what the entertainment industry never accessed. Hip Hop went on a global mission to unify the world, but the Bay Area’s inner-city culture remains a world unto itself. “The Day Before Hip Hop” — which deserves to be fully documented by today’s academic scholars & curators — is a term coined by the community-proclaimed cultural hero and international icon of San Francisco’s Strutting, Lonnie “PopTart” Green. Born in 1967 at St. Mary’s hospital and raised in both the Hunter’s Point and Fillmore communities, PopTart was adopted by San Francisco’s top-tier dancers as a child, and dubbed “The Fillmore Kid” by the inner-city’s most-feared personalities. An original Strutter whose dancing skill and choreography swept some of the biggest stages in Hip Hop, his understanding of both the entertainment industry and street politics over the course of 40+ years is unparalleled. What’s more remarkable is that his love for his community has always taken precedent over elevating his own name or fame. He never sold out and the streets know it. Now Lonnie Green is building with dancers, teachers and students from all over the world, educating them about the lost art of California’s inner-city Black dance culture, beginning with his own hometown of San Francisco. As CEO of Tart Productions International LLC, National Education Director for Hip Hop Congress, Inc., and founder of The Strutter’s Room, Lonnie’s lifelong mission is finally coming into recognition as he approaches the seasoned age of 55. The road hasn’t been easy. Lonnie grew up not being able to read, write or spell before dyslexia was a diagnosed learning disability, so he had to become resourceful in other ways. We now know the correlation between academic reading levels and the criminal justice system, because there is funding to test anyone for dyslexia in prison for free. As a community problem-solver, Lonnie grew up a fierce protector of people who are victims of the school-to-prison pipeline, and the SF police who were notorious for kidnapping and institutionalizing youth from their families while he was growing up. Today, Senate Bill SB 237 advocates for K-2 universal screening for dyslexia for which Lonnie is an outspoken spokesperson. When SF Mayor London Breed went on record in 2020 to thank Lonnie and declare Strutting a San Francisco treasure that is internationally recognized by some of the best dancers in the world, it became clear that SF’s Black community now has all the cultural positioning it needs to solve its most critical and visible problems — from homelessness to youth violence. But that doesn’t mean the financial resources of San Francisco are easy to access, even an international star like PopTart has to navigate a bureaucratic ocean of competitive organizations vying for equal attention. Lonnie is not alone. There are many like him, like Carlos Levexier, a former Strutter-turned champion wrestler who knows the importance of solidarity and whose transformational work in youth violence-prevention needs to be fully-funded, elevated and supported. Or Andre Dow, aka Mac Minister, who has served 16 years of a quadruple life sentence but is now set to receive a new hearing after the lead witness in his trial recanted their entire testimony. Figures like these are heroes in the community and threats to corrupt city politics. At one point, Lonnie himself faced a public smear-campaign labeling him a terrorist simply because of his influence in the streets, due largely to his Strutting ability. Less publicized is how Green used his influence to end the SF Turf wars between the Hunter’s Point and Fillmore communities in the 1990’s. The trauma in the SF Black community runs deeper than most can comprehend, narrated by a rap scene that speaks a language the city doesn’t permit in public venues. The effect of local corruption since the 1940’s on behalf of politicians, corporations and lawmakers has caused too many wrongful deaths and convictions over the years and is not going to fade away. Those who have not been affected by these injustices are in no position to solve them. There are many community leaders who hold positions of access who did not grow up in San Francisco, so their stake in the community is different. This means important inner-city voices often fall on deaf ears instead of being actively sought after for inclusion, which is the opposite of democracy. With collaborative efforts between yearly events like the Juneteenth Festival and the Annual International Strutter’s Room Master Camp which attracts dance students and teachers from all over the world to learn from SF’s inner-city culture, the resources to bring all of this information into light should automatically align, and not show up as an afterthought. We can learn from Breakin’ In The Olympics how organizing street culture is no small task, especially if you are not working from within the community that cares most about it. Individuals attached to external funding sources are likely to put their own power and positions over others, which breaks up solidarity and prevents important voices of the community from getting recognized properly. Lack of education leads to poor organizing which leads to a younger generation missing the chance to see their own cultural heritage supported by their current favorite artists on the main stage of every local event representing Black excellence in SF. When a city’s own community leaves its most important voices to fend for themselves, a walk-in-the-park turns into uphill battle. San Francisco has a golden opportunity to learn from those who have been systematically pushed out of the spotlight and into the margins. This story will remain tragic until we align our personal roles and goals in changing the narrative.

There is a giant awakening on the West Coast with creativity that was born to entertain the entertainers, knowledge that was held to educate the educators, and the power to provide youth with timeless experience for reinventing the way they use their own resilience and natural intelligence. Hip Hop never died, half of its body has just been in sleep paralysis for almost 40 years waiting for the rest of the world to wake up and get it moving again. Unlike the Olympics, this West Coast game isn’t something that you can beat or join. It’s been waiting for its time to return, and is either going to beat, or join you.

2 Comments

11/17/2022 11:32:17 pm

Vote cause fight social work paper dark shake. Adult direction score certain analysis table back. True fish decade senior board rise one.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

HHC National Office

50 Woodside Plaza, #203

Redwood City, CA 94061

50 Woodside Plaza, #203

Redwood City, CA 94061

|

|

Hip Hop Congress, Inc. is a non-profit 501(c)3 corporation.

|

Click to set custom HTML

RSS Feed

RSS Feed